For many people, health and longevity can quickly feel overwhelming. We are often met with long training programs, complex dietary rules, and the idea that living healthier requires major changes and a lot of time. When everyday life is already busy, this can easily become a reason to do nothing at all.

But what if it doesn’t have to be that demanding?

What if very small, realistic changes in everyday habits are statistically associated with measurable differences in both how long we live and how many of those years are lived in good health?

In this blog, we take a closer look at findings from a large population-based study published in 2026. Using data from the UK Biobank, the researchers examined how modest, combined variations in sleep, physical activity, and diet were associated with differences in both lifespan and healthspan.

About the study

The findings discussed here are based on the study “Minimum and optimal combined variations in sleep, physical activity, and nutrition in relation to lifespan and healthspan.” The analysis draws on long-term follow-up data from the UK Biobank and focuses on how everyday lifestyle patterns relate to both length of life and years lived without major chronic disease.

Rather than asking what an “ideal” lifestyle looks like, the study asked a more practical question: how small do lifestyle changes need to be before measurable differences appear at the population level?

What is SPAN?

In the study, the researchers use the term SPAN to describe the combined role of:

- Sleep – nightly sleep duration

- Physical activity – daily movement, with a focus on moderate-to-vigorous intensity

- Nutrition – overall diet quality rather than individual foods or nutrients

These three lifestyle factors are well-established, modifiable risk factors for chronic disease and premature mortality. They also influence overlapping biological processes, including metabolism, inflammation, and energy balance.

Instead of analysing each factor in isolation, the SPAN framework treats sleep, physical activity, and nutrition as one combined lifestyle pattern. This makes it possible to examine how simultaneous variations across all three are associated with lifespan and healthspan within the same statistical models.

What was measured?

Sleep and physical activity were measured objectively using a wrist-worn accelerometer, worn continuously for seven days by a subsample of more than 100.000 participants. Participants were included if they provided valid data for at least three days, including one weekend day.

The device recorded movement across day and night, allowing researchers to estimate:

- average sleep duration

- overall daily movement

- minutes spent in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA)

Because activity was measured objectively, the data captured both planned exercise and everyday movement, such as walking, standing, and routine daily tasks.

Diet was assessed separately using a validated food-frequency questionnaire, from which an overall diet quality score was calculated. The score reflected habitual dietary patterns over time rather than individual foods or nutrients.

Together, these measures allowed researchers to examine how sleep, physical activity, and diet—both individually and in combination—were associated with long-term health outcomes.

Lifespan and healthspan

- Lifespan refers to the total length of life.

- Healthspan refers to how many of those years are lived in good health, without major chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or dementia.

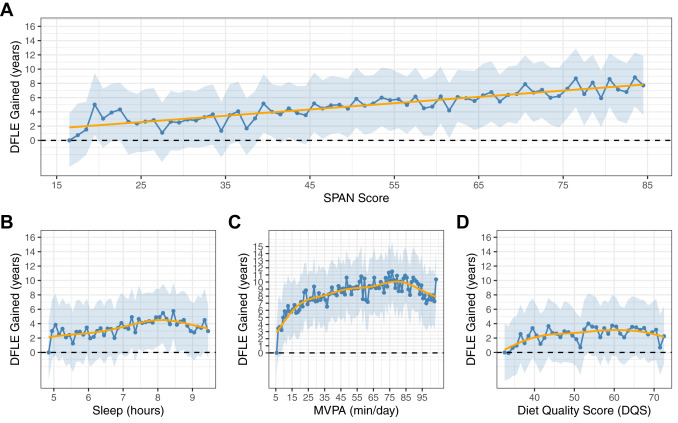

A key aim of the study was to examine whether changes in everyday habits were associated not only with living longer, but with living more years free from disease.

What did the study find?

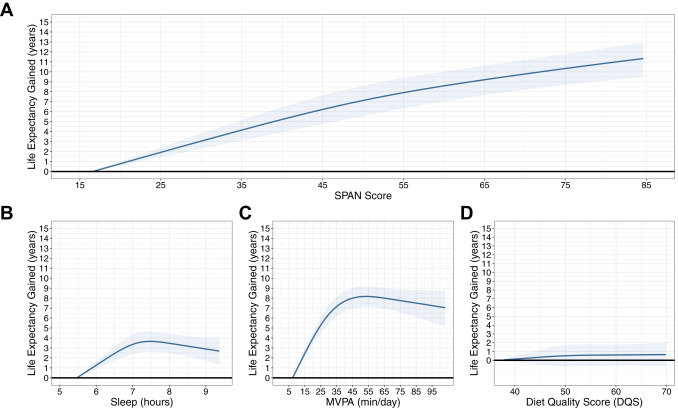

When the results are viewed as a whole, a clear pattern emerges: more favourable combinations of sleep, physical activity, and diet were associated with longer lifespan and more years lived without major chronic disease.

Importantly, the study highlights how small the combined differences can be before measurable associations appear in population-level models.

Small changes can meaningfully extend lifespan

Using statistical models, the researchers estimated the minimum combined variations in sleep, physical activity, and diet that were associated with approximately one additional year of life expectancy, compared with the least favourable lifestyle pattern observed in the population.

According to the model estimates, this corresponded to a combined pattern that included:

- around 5 additional minutes of sleep per day

- approximately 2 extra minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- a small improvement in overall diet quality, such as a slightly higher intake of vegetables

In other words, participants with the least favourable measured lifestyle would, according to the models, only need very small combined changes across sleep, movement, and diet to be associated with about one extra year of life expectancy.

Physical activity shows the strongest individual association

Among the three SPAN factors, physical activity demonstrated the strongest individual association with both lifespan and healthspan.

Even small increases in daily moderate-to-vigorous activity were associated with measurable differences, particularly when combined with improvements in sleep and diet. Stronger and more consistent associations were observed at higher activity levels.

Around 20–25 minutes per day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity was associated with meaningful gains in both lifespan and healthspan. Benefits continued to increase up to approximately 50–75 minutes per day, after which the association levelled off.

Because activity was measured using an accelerometer, these findings were not limited to structured exercise alone, but reflected total daily movement.

Sleep has a clear sweet spot

For sleep, the study showed a familiar pattern. The most favourable associations with both lifespan and healthspan were observed at approximately 7–8 hours of sleep per night.

Both shorter and longer sleep durations were associated with smaller benefits. Sleep on its own showed an association with outcomes, but its contribution became stronger when considered together with physical activity and diet as part of a combined lifestyle pattern.

Diet matters most in combination

When analysed on its own, diet quality showed a more modest association with lifespan. Improvements in diet alone were not strongly associated with longer life.

However, when diet quality improved alongside sleep and physical activity, it clearly contributed to the overall association with both lifespan and healthspan. The improvements reflected general dietary shifts—such as higher intake of vegetables, whole grains, and fish—rather than strict or complex dietary rules.

More years without disease require slightly more—but still not much

When the researchers focused on healthspan, the associated changes were slightly larger, but still modest.

In the statistical models, a combined variation equivalent to:

- around 24 additional minutes of sleep per day

- just under 4 extra minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity per day

- a clearer improvement in diet quality

was associated with approximately four additional years lived in good health.

At the most favourable lifestyle combinations observed in the study, the models estimated gains of up to nine additional years of life, with nearly as many of those years lived without major chronic disease, compared with the least favourable lifestyle patterns.

Small changes can make a difference

Taken together, the results point to one clear message: it is the interaction between sleep, physical activity, and nutrition that matters most.

Rather than requiring dramatic lifestyle changes, which can be difficult to sustain over time, the study suggests that small, simultaneous variations across these three areas were associated with meaningful differences in both lifespan and healthspan at the population level.

Seen this way, the findings offer a reassuring perspective. Supporting long-term health does not necessarily require extreme effort or perfection. According to the study’s models, even small and realistic changes—when made together—were associated with more years lived and more of those years spent in good health.

References

- Koemel NA, Biswas RK, Ahmadi MN, Teixeira-Pinto A, Hamer M, Rezende LFM, et al. Minimum combined sleep, physical activity, and nutrition variations associated with lifeSPAN and healthSPAN improvements: a population cohort study. eClinicalMedicine. 2026; Online first 13 Jan 2026:103741. Open access.

Track 50+ health metrics with AI-powered accuracy. Start your free trial today and take control of your wellness journey!

longevity tips best exercises nutrition diets healthy lifestyle

The art of living well a life that’s not measured by years alone, but by experiences, health, and joy!